Trent Novelist Sean Kane Welcomes a new School Year with a University Fall Reminiscence

Trent in High Autumn was Written for Founding President, THB Symons

September 14, 2022

To help celebrate a new school year and Fall on Symons campus, Sean Kane has shared an essay looking back at the early years of the university.

To help celebrate a new school year and Fall on Symons campus, Sean Kane has shared an essay looking back at the early years of the university.

“I wrote Trent in High Autumn for Founding President Tom Symons a month before he died,” recalls Sean. “Tom phoned me to tell me how much he was moved by it. He said the thing about Trent is that it has an indestructible soul. If people could remind the community every so often of its visionary spirit, Trent will continue to offer students what’s essential in the experience of a university.”

Trent in High Autumn features a cast of academic characters and uniquely Trent moments that are both poignant and comedic. It a literary scrapbook of woolly snapshots that could only have occurred on the bourgeoning Trent campus.

We are honoured to help Sean, and the late THB Symons, remind us all of the University’s unique beginnings, outlook, and ideals as a community of scholars.

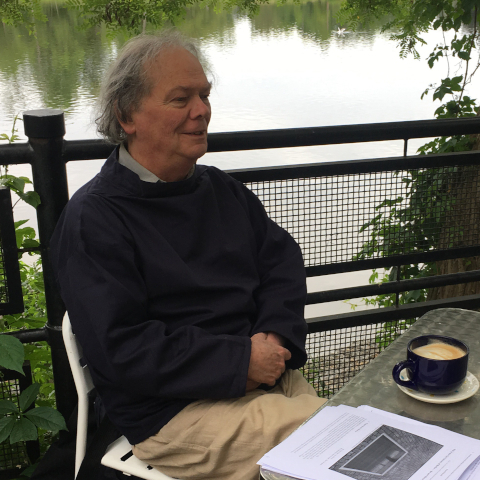

Sean Kane is a Professor Emeritus in English Literature and Cultural Studies. His second novel Racoon: A Wondertale will be published by Guernica Editions in March, 2023.

TRENT IN HIGH AUTUMN

It is high autumn in the land of universal higher education and all across North America people are remembering their alma mater. The hotels are packed for Homecoming Weekend. Football is in the air. The university band led by cheerleaders parades down the main street. Masses of students are singing arm-in-arm. The partying has already begun.

Up here in the Kawarthas, my thoughts turn to Trent University which has none of the above except a nostalgic memory. The year I joined, it boasted in its Calendar: “Trent is the smallest and one of the youngest universities in Ontario and it has no ambition to compete in size, but rather in excellence.” That year, it had close to 2000 undergraduates and a few graduate students and was about to earn the title that would define it for the next quarter century: Canada’s Outstanding Small University. I think of the golden hazy days between the Canadian Studies field-trip to Camp Wanipetei and the Head of the Trent Regatta. The cool northern air. Geese flying overhead. Students pile off the Trent Express, chattering with excitement. The stone façade of Champlain College exchanges secrets with the drumlin, its crimson sumac pressing through the early morning mist from the river like a Japanese watercolour. We were blessed. Thirty years of existence in a social ideal that is impossible in the world today – a university without an administration.

Arriving to join the faculty at Trent, I found myself in an Alice-in-Wonderland storybook where no one seemed to be an academic. This was odd. At the University of Toronto where I was previously appointed, conversation might range from an important book just reviewed in the Times to an idea raised by a colleague in a recently published paper, which was gently evaluated and praised. But at Trent, no one claimed to be interested in books or ideas, let alone the activity called research. It was a social blunder to even raise the topic and risk appearing professional and therefore boring. Many of my new Trent colleagues had studied at Oxford where it was the style to assume a cavalier superiority to routine mental labour, particularly that curse of the academic world, dynamic mediocrity. What did we talk about then?

We talked about our own Trent University, of course! Its students, its mission, its crises, its alarming rise in the size of a seminar group (“as many as 10!”), its new arrivals, its future. In short, we talked about ourselves. This is how a self-determining community survives. Because for a community to fashion itself daily there must be an ongoing conversation. And if the conversation is to have a theme that is open to everybody it has to be the vision of who we are and what we might become. Accordingly, much of the institutional decision-making at Trent happened in College Senior Common Rooms and Dining Halls. Then it extended to the network of committees designed to involve faculty directly in the work of institution-building. By these multifarious routes, decisions reached administrators who were themselves mainly drawn from the faculty, while continuing to teach part-time in offices dispersed among the colleges. There was no centralized suite of managerial offices, and to this day Trent has no administration building. Tom Nind, the president and vice-chancellor during the Seventies, worked from his teaching office at Traill College. After he retired, he joined the undergraduate population and audited the course on Shakespeare. For more than half its history, Trent was the only university in North America run by its faculty and students.

Of course, this conversation going on in the collective mind of the community couldn’t sustain itself for long without descending to the personal. Ascending is a better word, because at Trent telling anecdotes about colleagues was practiced as an artform. The best gossip was benign and generous, and brought out the humanity in whoever it touched – their quirks and idiosyncrasies, the small defining acts that made them human. The Master of Champlain had a dachshund whose consuming passion was chasing the chipmunks in the college quads. While the Master was in England on sabbatical, care of the college and its iconic dog passed to the Senior Don (a professor living in residence). It was his habit to scoop up the corpses of ducks he hit accidentally with his car on the River Road, and store them in the college freezer. So when the beloved dachshund died of a heart attack while chasing its last chipmunk, it seemed obvious to the Don to place its mortal remains in the college freezer, along with the hot-dog wieners and hamburger patties, awaiting spring when the Master would return and give his dog an Anglican burial (the Master was a churchman). In stories like this we saluted the human in each other and in ourselves. During my first year in the Trent community, I came to know my colleagues through the stories that were attached to them, long before I encountered them as people. Existence in the shared imaginations of their peers gave individuals a legendary quality.

A figure from the 1920s delivers a passionate lecture, becoming younger and racier as he recalls his youth. A gentleman-archaeologist right out of an Indiana Jones movie, he recalls hanging out in the cabarets of the Weimar Republic with Christopher Isherwood, the English novelist and screenwriter. Now another figure, elegant and reserved. He talks to a dozen sleepy English majors at the Friday morning Honours Colloquium about his challenges translating Shakespeare, Dickens and James Joyce, as well as several of the classics of German and American literature into Spanish. The following week he went to Spain and addressed thousands. This elegant poet turned out to be José-María Valverde, esteemed in the Spanish-speaking world for resigning the Chair of Aesthetics and Philosophy at the University of Barcelona during the period of the Franco regime, reassuming the chair when the dictator died. Stories first, who’s who come later in an oral community. I learned subsequently that the classical archeologist was Gilbert Bagnani who with his accomplished wife Stewart were artistic and academic stars in Toronto and abroad. Reputations are local, regional, national or international. The Founders of Trent took care to place a scholar with a national or a world reputation in every university department. Among us as we taught and learned, an unassuming academic excellence went unnoticed.

Collegiality concealed achievement; it also concealed laziness and failure. And it did so with an insouciant, almost blissful self-satisfaction. The affable head of the French department couldn’t speak French. A brilliant but dyslexic historian had his secretary rewrite his lectures. The more amiable a colleague, the more likely they were to have renounced research altogether. The opposite was true of the melancholy professor who was said to own a family castle in Scotland. One of the only three faculty who applied for research grants to the committee I chaired during my first year at Trent, he came to my office to introduce himself, looked at me balefully, and confessed with Calvinist gloom: “I hae’ failed ta’ achieve wha’ was expected o’ me.” In fact, he achieved significant and substantial research. What he couldn’t achieve was reading an undergraduate essay. Every student at Trent knew he scanned only the first page and the bibliography, then assigned one of three evaluations: “Very cogent,” “Cogent,” “Needs to be more cogent.” When Leah, to prove a point, submitted her essay for Women’s Studies sandwiched between a self-written first page and a bibliography culled from magazines in the Champlain SCR, she received the essay back overnight with the comment “Very cogent.” To be fair, there were several colleagues in the humanities and many in the sciences and social sciences who published regularly. A few diverted a creative intelligence into their teaching, producing variously a Bloomsbury Group complete with wine and etiquette; a Left Bank salon where questions of authentic existence hung in the smoky 20th-century air; and the Magic Circus Theatre Company which involved an entire course in the months-long activity of producing and staging a play, some performed in ruined ampitheatres on the Aegean. This “freedom to teach in a style that suited one’s enthusiasm met a sense of giddy exploration of one’s interests” among the students. The speaker is Lorraine, who transferred from a college in Vermont where she was overlooked. At Trent, she found “real people, stopping and talking together, not passing by with a furtive glance. We were a collection of people who ate dinner together, scrambled to get our assignments in on time together, went to Hallowe’en parties together.” For myself, teaching creative writing, I’m sure I learned a style of continuous suspense and surprise from the Frank Lloyd Wright principle of compression, then sudden expansion of space embodied in Trent’s architecture. For Gordon Teskey, a backeddying effect in the Otonabee became inspiration for an idea. Now 46 years later as Francis Lee Higginson Professor of English Literature at Harvard he writes in his award-winning Spenserian Moments about looking down from the Bata Library at that “‘wildest and most beautiful of forest streams,’ as Susanna Moodie called it … on the river running past and, despite the current, on the places where the green trees on the banks were reflected in the stream. In that moment everything seemed, for just a moment … gathered together and held, as if nothing had ended but simply moved past into something else.” So in Spenser’s narrative, “the moment flow together in that river of time where poems and readers are carried together.” Exceeded expectation, a sense of wonder, becomes a theme in the lives of a community set in nature, walking from building to building between classes.

A community treats its members as kin. As a result, whole cycles of life are witnessed by all. Eight colleague-and-colleague or colleague-and-student marriages were formed in the free to be you, free to be me culture of Trent’s Peter Robinson College. Seven children from these unions would become students at Trent. The divorces, the illnesses, the addictions, the mental breakdowns – all were part of the life of the community. A colleague at Lady Eaton displayed his dementia for the greater part of a year by opening the heavy front door of the college for anyone who entered. The colleague who started The Magic Circus Theatre lived out the final stages of AIDS hosting a daily symposium across the street from Robinson College. They served the community right to the end. Another colleague, who was given to writing Greek quotations from Thucydides on post-its and sticking them to the walls and ceiling of his office, was tolerated so long as his students felt they were learning something. He subsequently disappeared into his erudition and was all but forgotten. But at a small funeral arranged for him by his colleagues, Thomas H.B. Symons, the Founding President of Trent, attended, just as he had attended the public retirements and funerals of faculty for over 60 years. It would be fitting to close with his vision of education which made this community possible. (I quote a fundraising brochure from about 1970, titled An Individual Experience).

Trent University is unique amongst the universities of Canada …

The organization of the university into a system of residential colleges has the same academic purpose as its teaching methods: to bring faculty and students together within small communities where each person has an identity and where students and professors of all disciplines can live, talk and work together. Within the residential and teaching college, living and learning become one process and the student becomes a member of a community that is far more personal than the larger university of which the college forms a part.

The mission statement goes on to share the University’s plan for the next ten years: “In the future, further new buildings on the Nassau campus will grow outward from the original core and eventually 12 to 14 colleges will stand by the river … to accommodate an anticipated enrollment of 4000 by 1980.” There would be a second bridge, thereby embracing the university community in a giant pedestrian circle so that, as the master architect updating the plan in the year 2000 explained, “Students will always be passing through each other.” Passing through each other, like memories.

A university village! A place where everyone is elevated in the enchantment of higher learning. Corporate donors and charitable foundations must have blinked at this quixotic investment in a social ideal. It was certainly over the top. But to give a student the experience of people living and learning socially – their joys and setbacks, their vulnerabilities and courage, in sum their humanity – it was worth every penny. (1990 words)

Raccoon: A Wondertale by Sean Kane with Afterword by Margaret Atwood (Guernica Editions, 978-1-77183-782-8) features a community of well-known Canadian authors disguised as birds and animals surviving on the Otonabee in the age of crisis ecology. Available for pre-order in October.